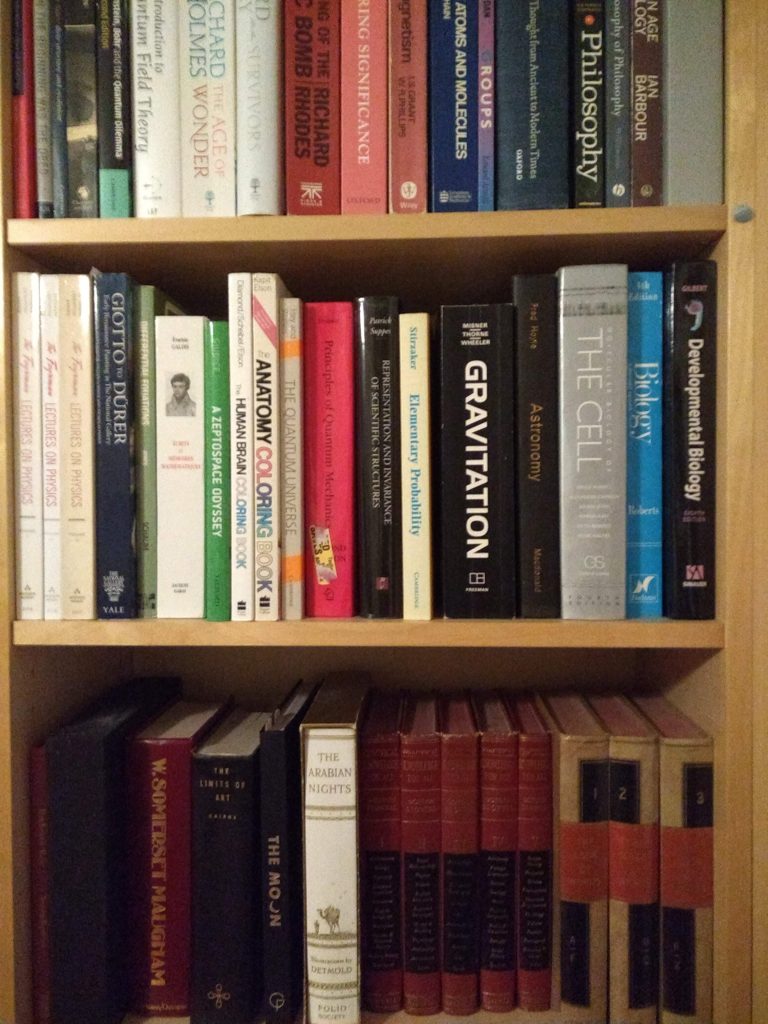

If the space in this room represented all the useful, interesting, well-evidenced knowledge we’ve accumulated in human history, each piece wrapped up into a tiny, tiny pinpoint, the disciplinary knowledge we teach in schools would fit into the space of your little finger. How do we know this is the vital bit to teach our kids?

In the 1980s, education in England took a turn away from rote-learning and memorisation: the O-level was replaced with the General Certificate of Secondary Education. The point was to make the qualification accessible to all, there being a general feeling in the air that rote-learning and memorisation didn’t deserve the importance that O-levels attached to them. The new qualification would include coursework and would attempt, as best it could, to assess skills.

In the second decade of the twenty-first century, England took a turn away from coursework and skills assessment. The GCSE was to be made more rigorous and to mark the change it was rebranded with a new grading system. There was a general feeling in the air that the qualification had become too easy, that coursework grades could be manipulated and were all too often meaningless.

The swing back to an education system that places knowledge at its heart is a backlash that has been a long time coming. It’s a familiar story in education: the longer we tread one path, the more we appreciate its disadvantages and the louder the voices become calling for us to turn back. As I listened this week to a conference presenter, at a gathering of middle and senior school leaders, propounding all the benefits of a knowledge-rich curriculum, there was a sense of fatigue in the audience. The oldest teachers in the room had taught in a school system that put a high price on memorisation and rote-learning, long ago.

There are many reasons why, when we embark upon another great-grandfather pendulum swing of education, we do it in ways, right from the beginning, that mean that one day we’ll be coming back. At the moment, we’re planting all the seeds to ensure that one day we’ll be rejecting the current working concept of a knowledge-rich curriculum. Because we are thinking about it too simply and implementing it too extremely. There were reasons we once turned against asking all students to memorise the same set of facts, and we need to remember those reasons, and take them into account as we embark upon building knowledge-rich curriculums (which could mean so many things).

A knowledge-rich curriculum could be one in which we help students to appreciate that, in order to evaluate, criticise, and assess arguments and information presented to us, we do so better if we’re platformed by a wealth of relevant knowledge. What we would mean by ‘knowledge-rich’ is that we will teach students the value of knowledge. We’d teach them to seek it out themselves, to distinguish it from fake news, and to ask questions like: how might more knowledge change my opinion? what would I need to know to form a evidence-based view on this topic?

A knowledge-rich curriculum could be one in which we ensure that future generations will have a wide variety of knowledge to share – that they won’t all have been taught the same thing but will bring different knowledge to the teams of tomorrow’s workplaces. What we could mean by ‘knowledge-rich’ is that we offer a wide variety of courses, each containing interesting, detailed, valuable facts that a student could learn and that would differentiate him or herself from others.

A knowledge-rich curriculum could be one in which students are taught about the mechanisms by which we generate it knowledge, how to access it, how to identify it. It could be one that teaches students about our knowledge-rich world, about how knowledge is used and how it can be powerful.

A knowledge-rich curriculum, however, could be one in which there’s simply a lot of things to learn, or one that drills down down deeply into a few areas.

But, in fact, none of these things is what our current working concept of knowledge-rich curriculum is looking like, as the concept is being applied, for example, by Ofsted. The inspectorate’s 2019 framework assesses the quality of curriculum, in terms of its content, breadth, and sequencing. There have been rising complaints that Ofsted has too often and too easily taken a negative view of schools which teach GCSE courses over three years. At one school, Ofsted criticised the lack of breadth of its curriculum for students aged 13-14, having allowed them to give up history or geography. The school takes all these students off curriculum on a Wednesday afternoon, to offer a choice of more than 50 activities (currently including Anglo-Saxon history, Japanese and fencing). In practice, the government’s concept of a knowledge-rich curriculum is tightly bound to its belief in the English baccalaureate. First and foremost, a knowledge-rich curriculum is one that contains a core set of knowledge in the primary disciplines. And it assumes that we have the disciplines right to begin with: a tiny amount of history, mathematics, English, physics, chemistry, biology, French (or suitable alternative), geography and computer science. That’s the most important bit of the huge amount of knowledge humanity has collated, the bit in the space of your little finger.

The fact that we came to promote this bit of knowledge more than others is more the accumulation of many accidents of history than we acknowledge. And when you get to learn some of the knowledge that sits outside of the school curriculum you might begin to wonder two things. Firstly, you might question the prioritisation of a few disciplines, when there are so many. And you might think that it’s not so obvious that the stuff in the finger space is always necessary to learn first. There’s not such an obvious place to begin on learning about our world, our society, and our place in it.

If we interpret a ‘knowledge-rich curriculum’ really to mean nothing more than the learning of particular facts in history and geography and science especially, we are implementing it crudely and extremely. We’ll soon remember why, for many years, we felt that the most important thing about education was the gaining of a particular set of skills in history and geography and science, and the voices will call ever louder to prioritise something else over knowlege.

There is a working assumption behind the concept of a ‘knowledge-rich curriculum’ (and that needn’t be attached to that concept): there is a base knowledge, in a very limited number of subjects, that everyone should know. I was sitting behind a row of department heads, and behind me there were two headteachers. The presenter told us that young people should know these things so well that they would remember them five years after leaving school. Memorisation and rote-learning were good things, he said And of course they can be, but I caught the eye-roll of a teacher at the side of the room. There was fatigue in the audience. The lady next to me, longtime in the field of education, muttered despondently, “Deja vu… again.”